I crashed into bed about 23 minutes after I posted yesterday’s post, and there I remained, feverish and hazy, in and out (but mostly out) of consciousness. I was better but not 100% and the morning was mostly a blur of sitting on the couch watching videos. After Noon, I was tired again so I napped. Woke up hungry, as I knew I would be, so went out to get some food.

When I came home, I dived into playing The Outer Worlds, Obsidian’s new action RPG.

I’m only an hour or two into it but I already love it. Wandering around on a colony world with the design aesthetic of Firefly (with a tiny bit of Fallout mixed in), the game itself is gorgeous and rich in those small details that really bring a place to life. The brand names, the way NPCs speak and dress, and the background philosophies are all working together to paint a particular picture.

Some small spoilers for early game lore ahead. I’ll hide them below the cut.

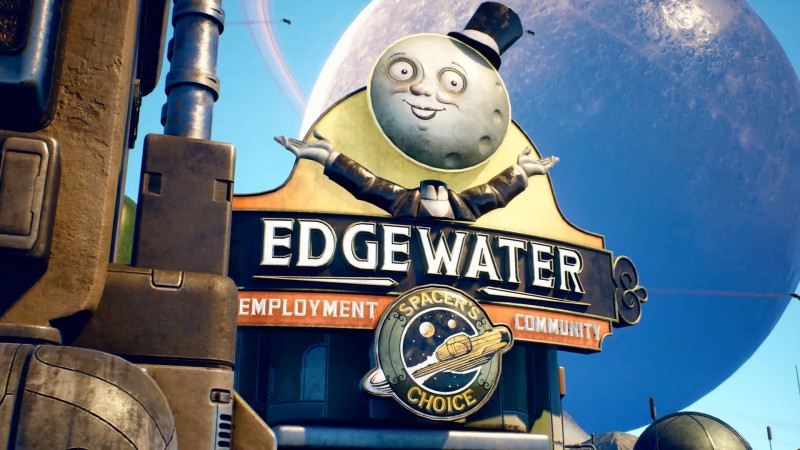

The town of Edgewater is a company town, owned and operated by Spacer’s Choice (“You’ve tried the best, now try the rest!” is repeated often enough, and in company literature, that it is not a misstatement.) Everything and everyone in town are there to produce a profit for the company, and human lives are expendable in that pursuit. Even talking to Silas, the town’s gravedigger—sorry, I mean Junior Inhumer—nets you a sales pitch and a sidequest to get some of the townsfolk to cough up the money the company charges to bury them after they’ve given their lives up through overwork.

There are signs of humanity, though, among the proletariat. You might encounter someone who officially works for Spacer’s Choice HR (technically she’s an actuary; she calculates what it costs to hire, feed, bury and replace a worker) who is willing to do some shady things to get medicine to them what needs it.

The town religion is The Order of Scientific Inquiry (OSI), colloquially known as Scientism, which to my mind reads like a mix of Calvinist theology with Enlightenment-era Deism. In Scientism, the universe is a great big machine, set into perfect, perpetual motion by The Great Architect—who promptly removed Themselves from its day-to-day running. According to Vicar Max, humanity’s purpose is to find, catalog, and calculate every single particle in the universe, at which point everything will be known: everyone’s place in the Great Machine, everyone’s destiny, the reason for everything that happened and will happen, at which point everyone will ascend to the status of Great Architects ourselves.

It’s a philosophy that meshes well with corporate overlords who just want people to do their jobs and not pay much attention to how things might be different. It’s a useful tool by which to beat down curiosity and cleverness that doesn’t serve the bottom line. It’s cold. Just like Edgewater.

When I play games like these, at least on my first playthrough, I always have trouble finding the path between two conflicting urges. On the one hand, I want to try everything, speak every dialog option, see every possible outcome of every single side-quest, even if that leads me to doing things in the game I would never do. On the other hand, I want to be myself: someone who looks out for the little folk, someone who is resistant to authority, someone who doesn’t demand a reward for choosing the moral choice in every situation.

In The Outer Worlds, at least so far, it’s been very easy seeing the paragon path in most circumstances. I mean, you know me, if you’ve read this blog enough. You know I am no fan of capitalism. And in The Outer Worlds, Obsidian is very definitely making an anti-capitalist message.

I love it.